Table of Contents

How Charlie Health’s Virtual IOP is Improving BIPOC Mental Healthcare

Written By: Komal Kumar, MS

Clinically Reviewed By: Dr. Kate Gliske

February 17, 2023

7 min.

BIPOC Youth face distinct mental health challenges and a significant lack of access to effective mental healthcare, leading to historically poorer mental health outcomes. Charlie Health’s BIPOC program is changing this through high quality, culturally-specific care for its BIPOC clients, yielding equitable outcomes for both BIPOC youth and their non-BIPOC counterparts.

Learn more about our Clinical Review Process

Table of Contents

Contributors:

Dr. Chelsi Clark, Ph.D., NCSP, LPC, Director of BIPOC Programming

Kaycee Branch, Research and Clinical Outcomes Team

Background: BIPOC mental health challenges

Clients who identify as Black, Indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC) face distinct mental health challenges and have unique needs based on their lived experiences and identities. As the population of minority groups in the U.S. increases, BIPOC youth are experiencing increasing disparities in their mental health and continue to face significant barriers to receiving high-quality, culturally-specific mental healthcare. BIPOC youth are a particularly vulnerable population, as the intersectionality of the inherent vulnerabilities related to youth and adolescence are magnified by the effects of structural, interpersonal, and internalized racism.

BIPOC clients contend with several barriers to accessing mental healthcare. For one, BIPOC communities experience higher mental health stigmatization and implicit bias from clinicians relative to the general population. Mental health stigma and bias are associated with poor service utilization (as in, seeking out and accessing mental health services) in these communities. Another barrier is racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage, which also impacts mental healthcare accessibility. For example, African Americans and individuals of Hispanic descent persistently have lower insurance coverage rates across all ages compared to non-Hispanic whites. BIPOC populations also tend to experience higher rates of poverty and homelessness, which negatively impacts their ability to access medical care in general, including mental health services.

Existing research on BIPOC mental health services is quite limited compared to research on mental healthcare in white populations. Available literature generally supports the importance of culturally-specific care that incorporates a number of crucial elements into BIPOC mental healthcare programming, including the following:

- Clinicians that have undergone cultural competency training

- Ethnic and racial matching between clinicians and clients

- Addressing racial trauma within the programming

- Utilizing integrated or “whole person” models of care, which involve addressing a patient’s individual needs as well as their specific environmental and behavioral context in care

Despite this theoretical consensus on what BIPOC mental healthcare programming should look like, very few concrete examples of this type of programming have been implemented in practice. This lack of access to high-quality care has historically led to poor mental health outcomes for BIPOC individuals relative to their white counterparts. A wealth of literature shows that while racial minorities have higher rates of mental health disorders than white individuals, they often experience worse clinical outcomes and greater mental health disparities, highlighting the need for better and more accessible mental healthcare for BIPOC individuals.

BIPOC programming at Charlie Health

Charlie Health is a nationwide virtual IOP program for adolescents and young adults struggling with a variety of mental health disorders. In order to meet the needs of all the youth served, Charlie Health offers a variety of curated groups based on demographic characteristics, lived experiences, and mental health conditions.

BIPOC programming at Charlie Health offers young people the chance to be in spaces where their peers and counselors look like them and talk like them, in sharp contrast to their lived experiences where they are often othered. In contrast to general programming, BIPOC programming is focused on lessening stigma and bias through racially and culturally-sensitive therapy. Care delivered in this fashion has been shown to increase participation, belongingness, satisfaction, and treatment outcomes among BIPOC clients.

One key component of Charlie Health’s BIPOC programming is ethnic and racial matching in which clients and therapists are matched based on shared race or ethnicity. This is beneficial in several ways:

- Matching has been shown to decrease the severity of mental illness in BIPOC clients.

- Visibly matching therapists and clients means that language-matching (when language unconsciously matches between interactional partners) can co-occur, allowing the client freedom of expression.

- Matching creates greater congruence between the therapist and their client, fostering a deeper therapeutic alliance and an increase in treatment participation.

The program’s curriculum itself utilizes evidence-based approaches to care that include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and relational therapy (RT), among others. For BIPOC youth, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is an important part of treatment since racial bias and victimization is a form of trauma exposure. In the program, young people of color can explore their experiences with their peers and therapists of color and explicitly acknowledge their traumatic stress, which is often the first step to healing.

This trauma-focused therapy also acknowledges the historical and cultural trauma of minorities and indigenous people, recognizing transgenerational trauma and intergenerational trauma. Addressing all types of trauma, TF-CBT incorporates ways to gently and gradually expose the client to trauma experiences, including psychoeducation, relaxation, and affective modulation, among others.

Together, clients, counselors, and peer groups in the BIPOC program take deeper explorations into how race-based experiences affect mental health, all in a virtual setting. Since trauma-exposed racial minorities face greater barriers to receiving care, Charlie Health’s virtual IOP model serves as a critical vehicle in delivering racially- and culturally-sensitive TF-CBT.

Given the overwhelming evidence that treatments for BIPOC clients have historically lacked effectiveness and BIPOC clients experience worse mental health outcomes than white clients, we sought to explore whether clients in Charlie Health’s BIPOC programming demonstrated equitable gains in clinical outcomes relative to their white counterparts.

Data from the BIPOC clients of Charlie Health

In a sample of 3,442 adolescents and young adults who were admitted to Charlie Health’s virtual IOP program in the second half of 2022, approximately two thirds racially identified as single race white, while 27% identified as BIPOC.

We defined “BIPOC” as being based on racial identity (those who racially identify as Black, Indigenous, or a person of color). Historically, the concept of race has changed across cultures and eras, and has eventually become more concerned with physical characteristics as opposed to ancestral and familial ties. Ethnicity is similar in concept to race, but ethnic distinctions generally focus on cultural characteristics (like history, language, customs, and religion) as opposed to physical characteristics.

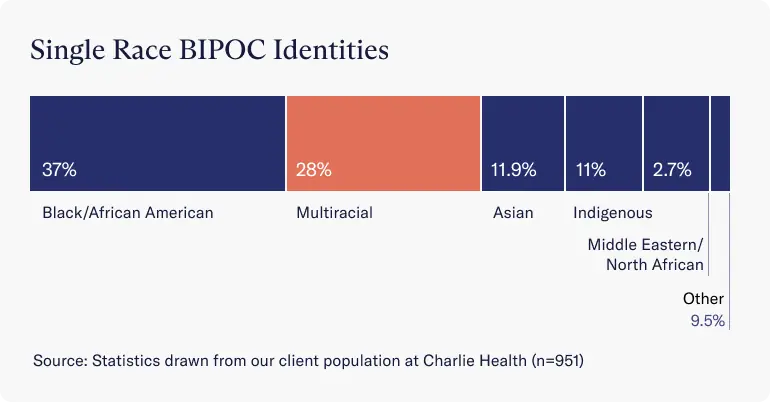

Looking more closely at those who identified as BIPOC, the largest subgroups were:

- Black and African American (37.3%)

- Multiracial (28%)

- Asian (12%)

- Indigenous (11%)

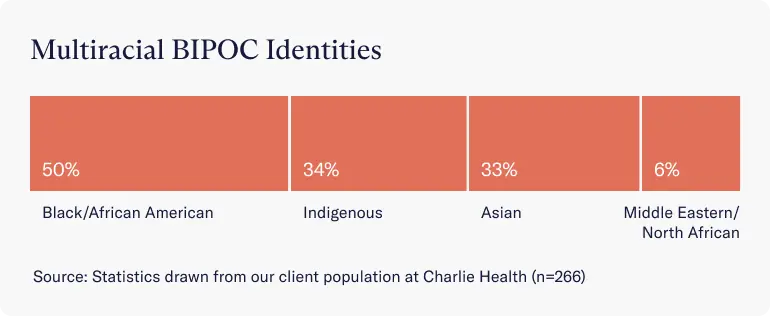

Within the multiracial category, the breakdown of single-race identities is:

- Black or African American identity (50%)

- Indigenous identity (34%)

- Asian identity (33%)

- Middle Eastern or North African identity (6%)

BIPOC Program Clinical Outcomes

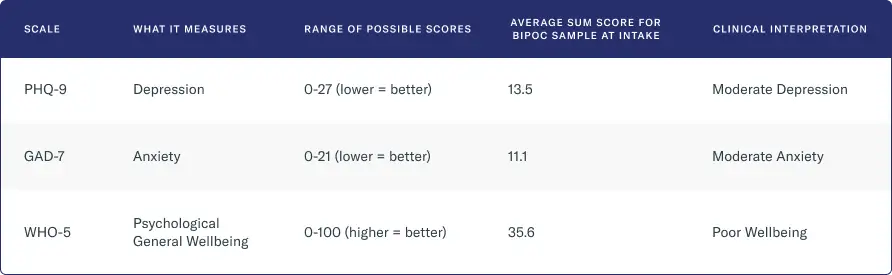

At intake, BIPOC clients presented with a range of mental health disorders, most notably:

- Moderate depression, as measured by the depression questionnaire PHQ-9

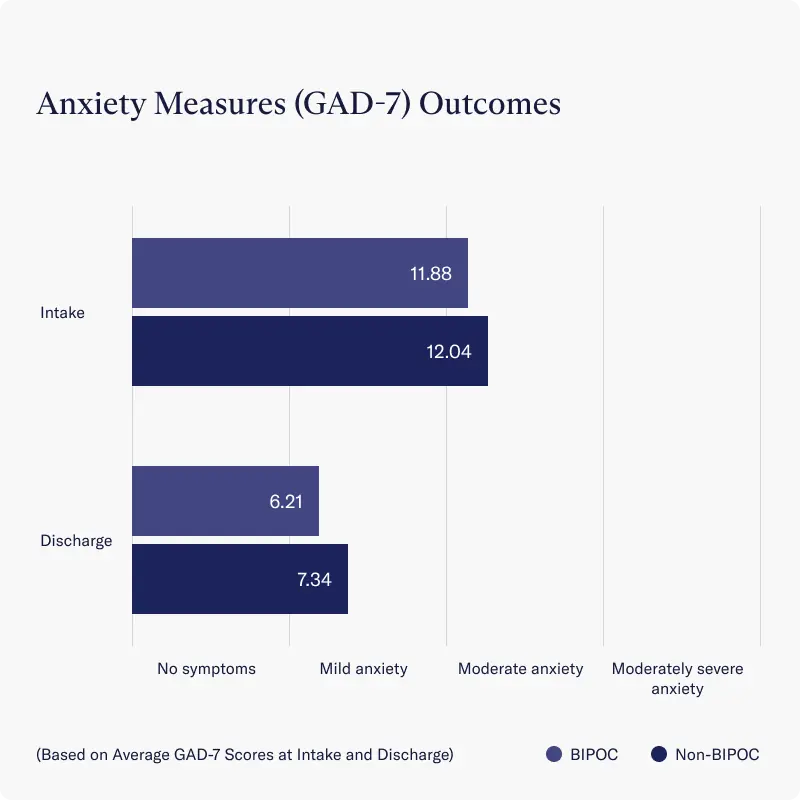

- Moderate anxiety, as measured by the anxiety questionnaire GAD-7

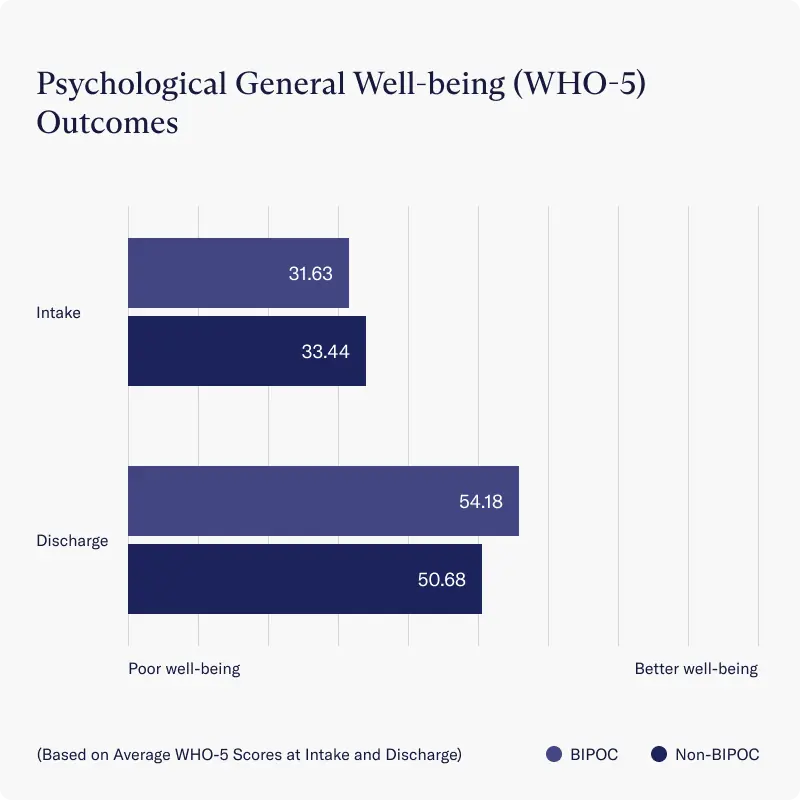

- Clinically poor well-being, as measured by the psychological general well-being questionnaire WHO-5

Many of these BIPOC clients choose to enter BIPOC-specific programming groups. As of early February 2023, Charlie Health runs four BIPOC groups with over 50 clients and over 50 culturally-competent, BIPOC-identifying facilitators. On average, individuals in the BIPOC program report being “very satisfied” with their group therapy sessions.

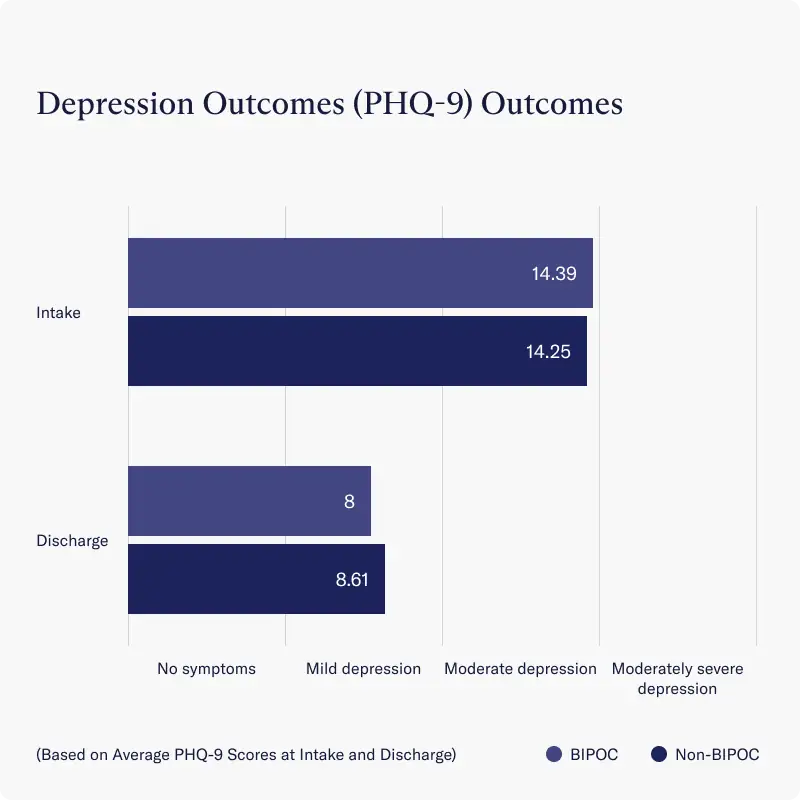

In contrast to the wealth of literature pointing to poorer mental health outcomes for BIPOC individuals, Charlie Health’s BIPOC groups show clinical outcomes similar to their non-BIPOC counterparts. In comparing change over time between BIPOC and non-BIPOC groups, no significant differences were detected, indicating that BIPOC clients are experiencing equitable improvements in mental health outcomes following participation in Charlie Health programming.

- Both BIPOC groups and non-BIPOC groups reported similar reductions in depression severity at discharge, as measured by average improvements on the PHQ-9 scale

- Across all clients, average depression severity decreased from moderate depression reported at intake to a score considered to be below the cut-point for diagnosing Major Depressive Disorder (PHQ-9 Sum Score <10)

Similarly, for both BIPOC and non-BIPOC groups, reported decreases in anxiety symptoms were statistically similar, as measured by average improvements on the GAD-7 scale.

- Both BIPOC and non-BIPOC groups experienced a reduction from moderate anxiety to mild anxiety (GAD-7 Sum Score <9) by the time they were discharged

Finally, both BIPOC and non-BIPOC groups reported significant improvements in psychological well-being, as measured by average scores on the WHO-5 scale, where higher scores indicate better well-being.

The importance of culturally-specific mental health programming

BIPOC communities face distinct mental health challenges and have unique needs. The high-quality mental healthcare services needed to combat the disparities they face are often not available or hard to access, and treatment offerings are rarely adapted to address the compounding effects of racism and intergenerational trauma on mental health.

Culturally-specific care should include culturally-competent clinicians, ethnic and racial matching, processing around racial trauma, and a curriculum that utilizes integrated models of care. Preliminary evidence from Charlie Health’s BIPOC program suggests that when culturally-specific mental health care is offered to BIPOC youth and young adults, they report improvements in their symptoms similar to their non-BIPOC peers.

Treatment providers must endeavor to provide the best, most personalized care available to their clients, and it is increasingly clear that core differences in lived experience must be directly addressed in programming if equitable care is to be provided to historically marginalized communities.

References

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1215487.pdf