Table of Contents

An Analysis of Risk Factors for Suicidal Thoughts and Outcomes at Charlie Health

Written By: Massimo Barczys

Clinically Reviewed By: Dr. Don Gasparini

September 26, 2023

7 min.

Understanding suicide risk factors and connecting young people with treatment is crucial for combating the youth suicide epidemic. This piece analyzes Charlie Health clients’ suicidal ideation risk factors and positive outcomes.

Learn more about our Clinical Review Process

Table of Contents

Trigger warning: Suicide. If you’re experiencing suicidal thoughts or are in danger of harming yourself, this is a mental health emergency. Contact The Suicide & Crisis Lifeline 24/7 by calling or texting 988.

The fight against suicide can, tragically, feel like an uphill battle. Rates of suicide have increased significantly since 2000, and more than 700,000 people die by suicide annually—a sobering number that experts argue could be even higher. In the United States, young people are increasingly at risk for suicide as the national teen suicide rate is rising. Data shows suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents and young people. To turn the tides on this crisis, it’s essential to identify and address the specific risk factors for suicide and offer immediate and long-term resources to address suicidal thoughts—all work that Charlie Health’s virtual Intensive Outpatient Program aims to accomplish.

Charlie Health data: suicidal ideation and suicide risk factors

As part of an ongoing quality improvement study, our Clinical Research & Outcomes team collects data from our clients using self-reported surveys to follow client trends, produce publications, and improve our quality of care.

Between May 2022 and August 2023, a sample was collected of approximately 4,000 teens and young adults who were admitted and discharged from Charlie Health. Only clients who completed an intake and discharge survey upon entering and leaving the program were included in this sample. Suicide risk was assessed using Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ), a suicide risk assessment tool used by healthcare professionals to identify those at risk of suicide.

Passive vs. active suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation, defined as thoughts of ending one’s life, is often divided into two categories: passive and active suicidal ideation. Passive suicidal ideation is when someone doesn’t have a specific plan to end their life but feels like they don’t want to live anymore or wishes they could just sleep and never wake up. On the other hand, active suicidal ideation is when someone has thoughts of ending their life and a plan for how to do so.

Both passive and active suicidal ideation need to be taken seriously, as they are both forms of suicidal behavior that can be harmful if not addressed properly.

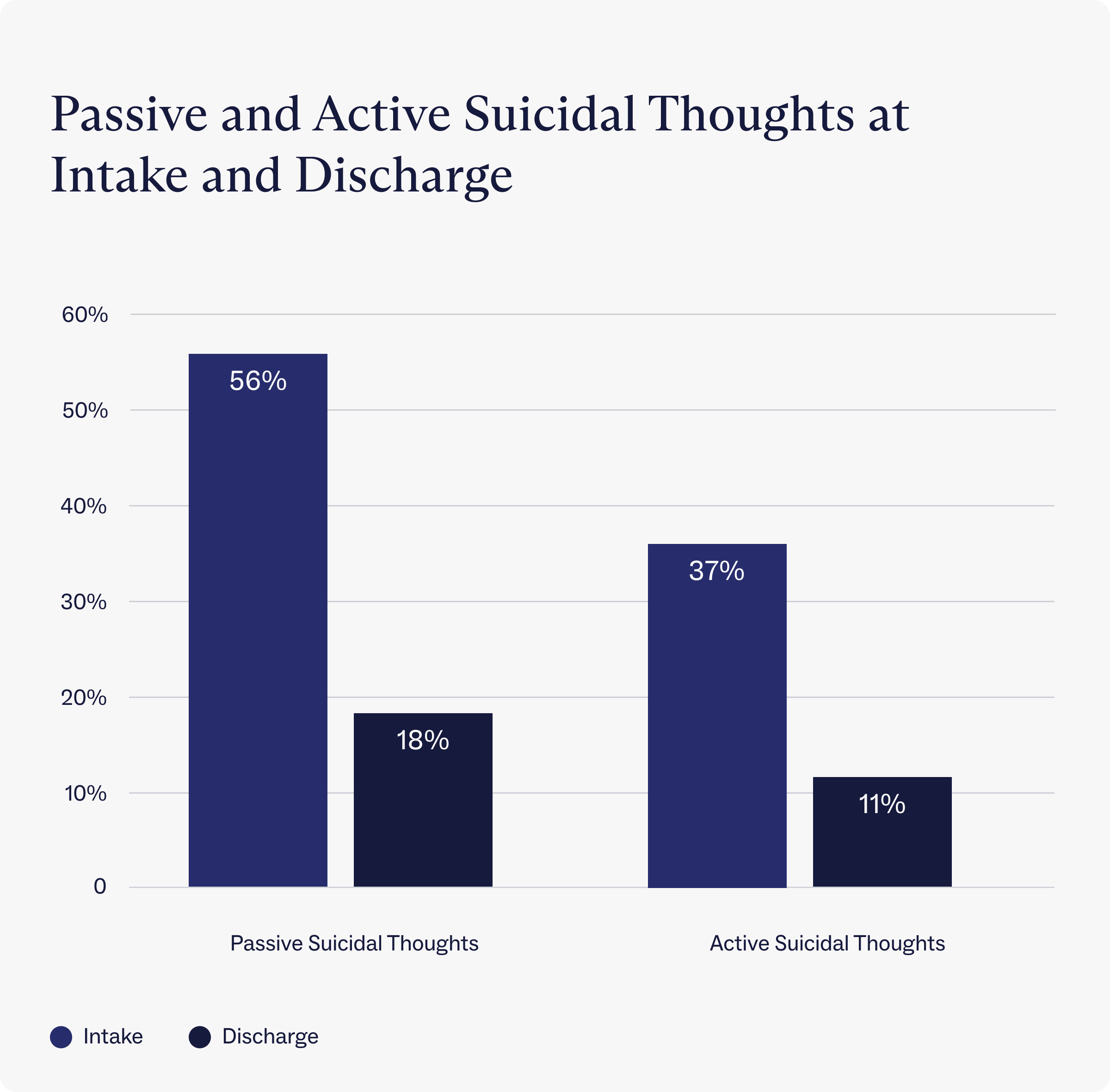

Data show that Charlie Health’s IOP reduces both passive and active suicidal ideation. At intake, over half (56%) of Charlie Health clients report feeling passive suicidal thoughts, but that number drops to just 18% at discharge. About one-third (37%) of clients at Charlie Health reported having active suicidal thoughts within a week of starting treatment, but that percentage decreased to just 11% upon discharge.

How to identify suicide risk factors

There’s no one cause of suicide, but by identifying risk factors, we can identify people at an increased risk for suicidal behavior and take steps to prevent suicide. The American Association of Suicidology developed a helpful mnemonic to remember the main risk factors for suicide, dubbed “IS PATH WARM,” which stands for:

- Ideation: thoughts of suicide

- Substance abuse: increased use of drugs or alcohol

- Purposelessness: feeling that there’s no reason to live

- Anxiety: agitation, sleep disturbances

- Trapped: feel like there’s no way out

- Hopelessness: feeling overwhelming despair

- Withdrawal: pulling away from friends and family

- Anger: uncontrolled rage

- Recklessness: engaging in risky acts

- Mood changes: dramatic shifts in mood

When assessing for suicide risk factors, it’s important to keep in mind that suicide is infrequent, and these risk factors are common, meaning someone could have several risk factors and not be suicidal. Also, the absence of any risk factors does not mean someone is safe from suicide.

While risk factors help assess whether someone may be at a greater risk for suicide, the most effective way to understand if someone is suicidal is to ask them directly. Some people may worry that talking about suicide could provoke suicidal ideation, but evidence shows that talking about suicide does not cause suicide. In fact, the opposite is true: talking about suicide can reduce suicidal ideation and help people get the mental health support they need, according to research.

Charlie Health data: suicide risk factors

In addition to the suicide risk factors mentioned above, there are certain demographic groups more at risk for suicide than their peers. Research shows that demographic risk factors for suicide include age, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, level of education, and genetics. As mentioned, environmental risk factors like substance abuse and recent stressful life events also play a role. Below, we analyze demographic risk factors associated with an increased risk of suicide and outcomes for Charlie Health clients.

Connecting the world to life-saving mental health treatment.

Learn more about our industry-leading outcomes for teens and young adults.

Gender and sexual orientation

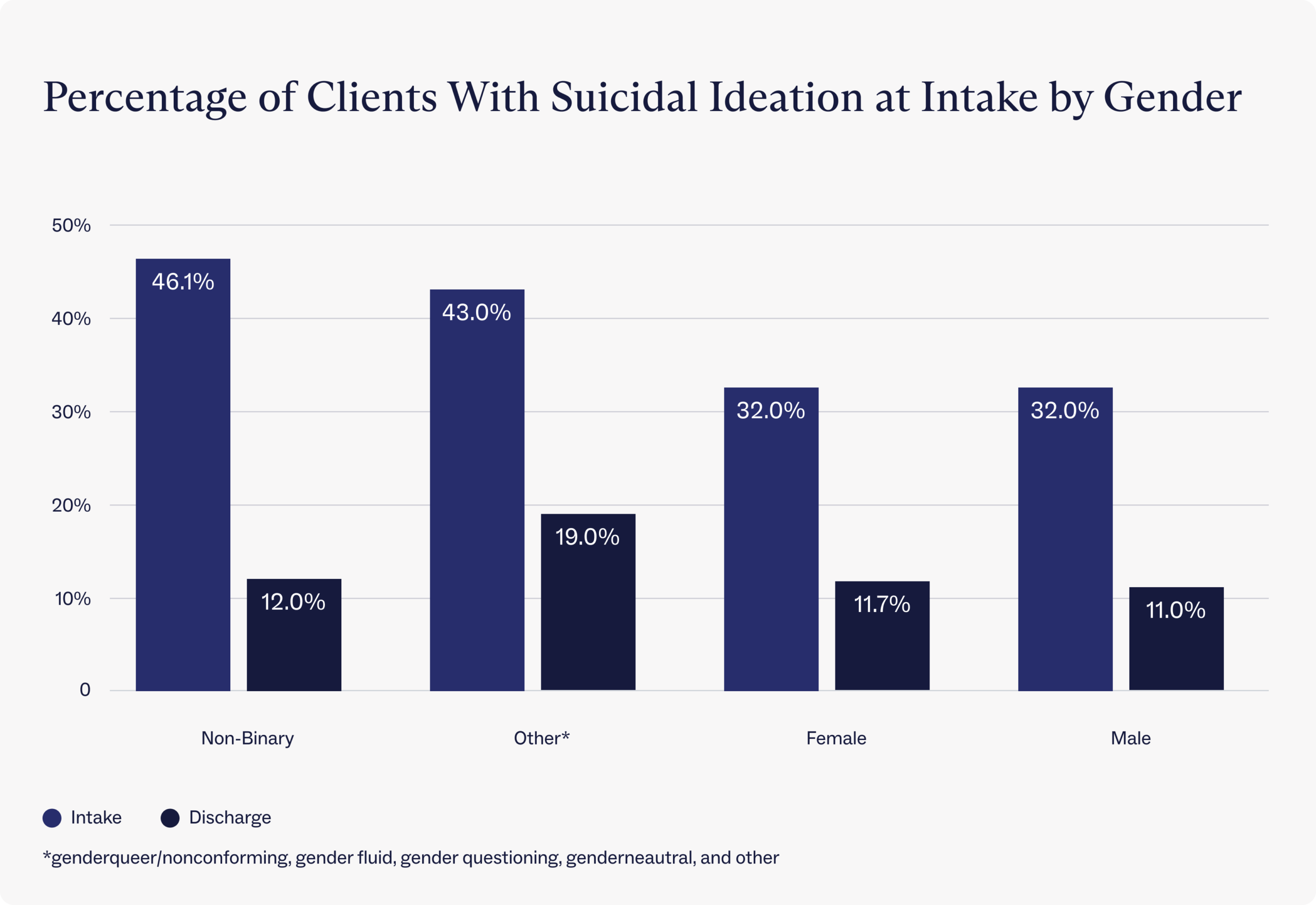

Existing research has found that transgender and non-binary clients show the highest levels of suicidal ideation among all genders, potentially due to decreased social support, increased stigma, and discrimination.

Research from Charlie Health substantiates that gender is a risk factor for suicidal ideation. Non-binary clients showed the highest percentage of suicidal thoughts at intake compared to all other gender identities: nearly half (46.1%) of the 167 non-binary clients surveyed reported suicidal thoughts. By contrast, about one-third (32%) of male- and female-identifying clients reported suicidal thoughts at intake.

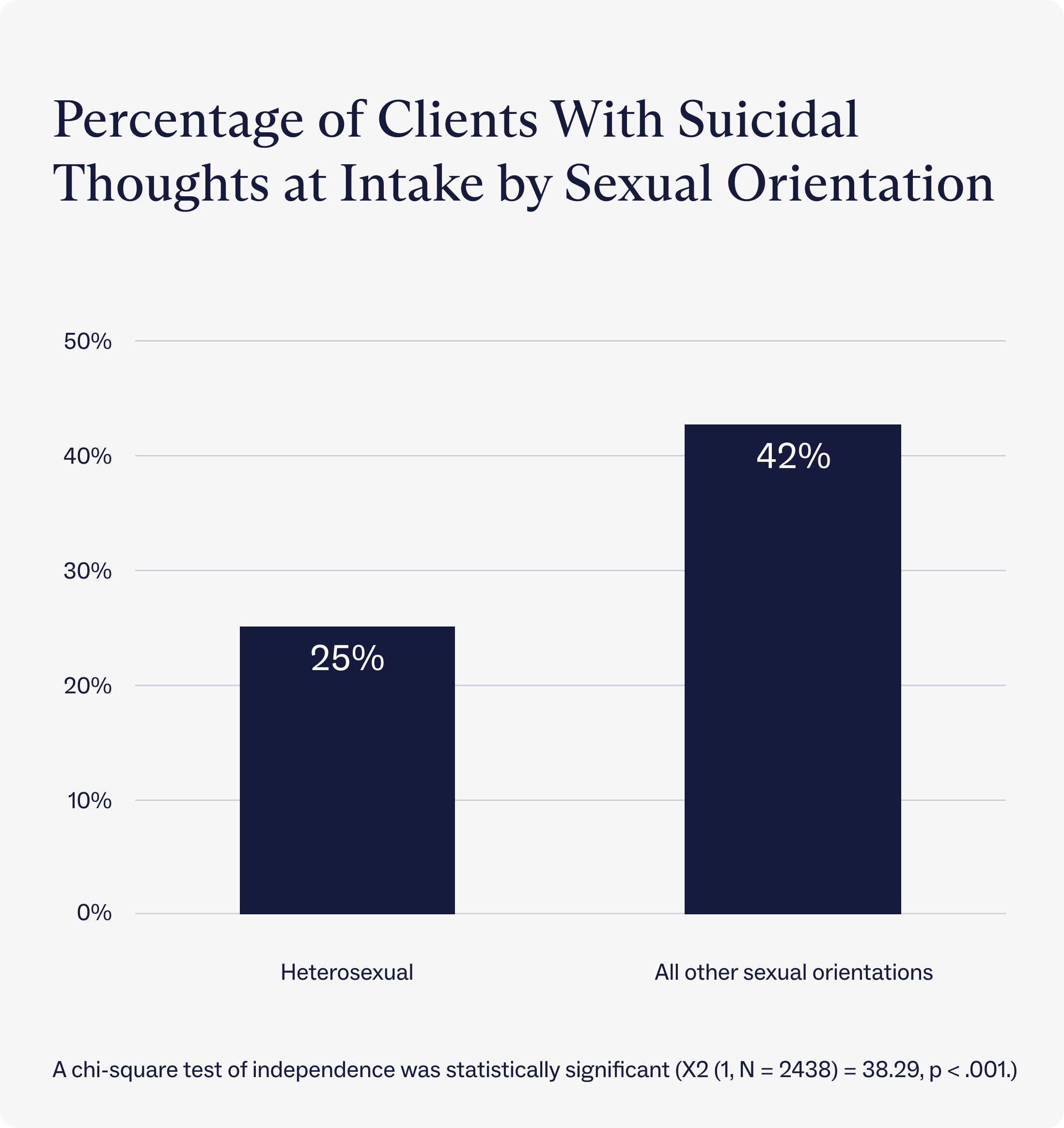

Similarly, LGBTQIA+ clients at Charlie Health showed a significantly higher amount of suicidal thoughts at intake (42%) compared to their non-LGBTQIA+ peers (25%). These findings are consistent with research showing that LGBTQIA+ people experience higher rates of suicidal thoughts.

At discharge, all genders showed major decreases in suicidal ideation. One potential reason for this significant decrease is Charlie Health’s use of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) skills, which have been proven effective in reducing suicidal ideation. Non-binary clients showed the greatest decrease in suicidal ideation, which may be due to Charlie Health’s DBT curriculum plus the increased social support in Charlie Health’s LGBTQIA+-specific groups. More research is needed to support these claims.

Work and school risk factors

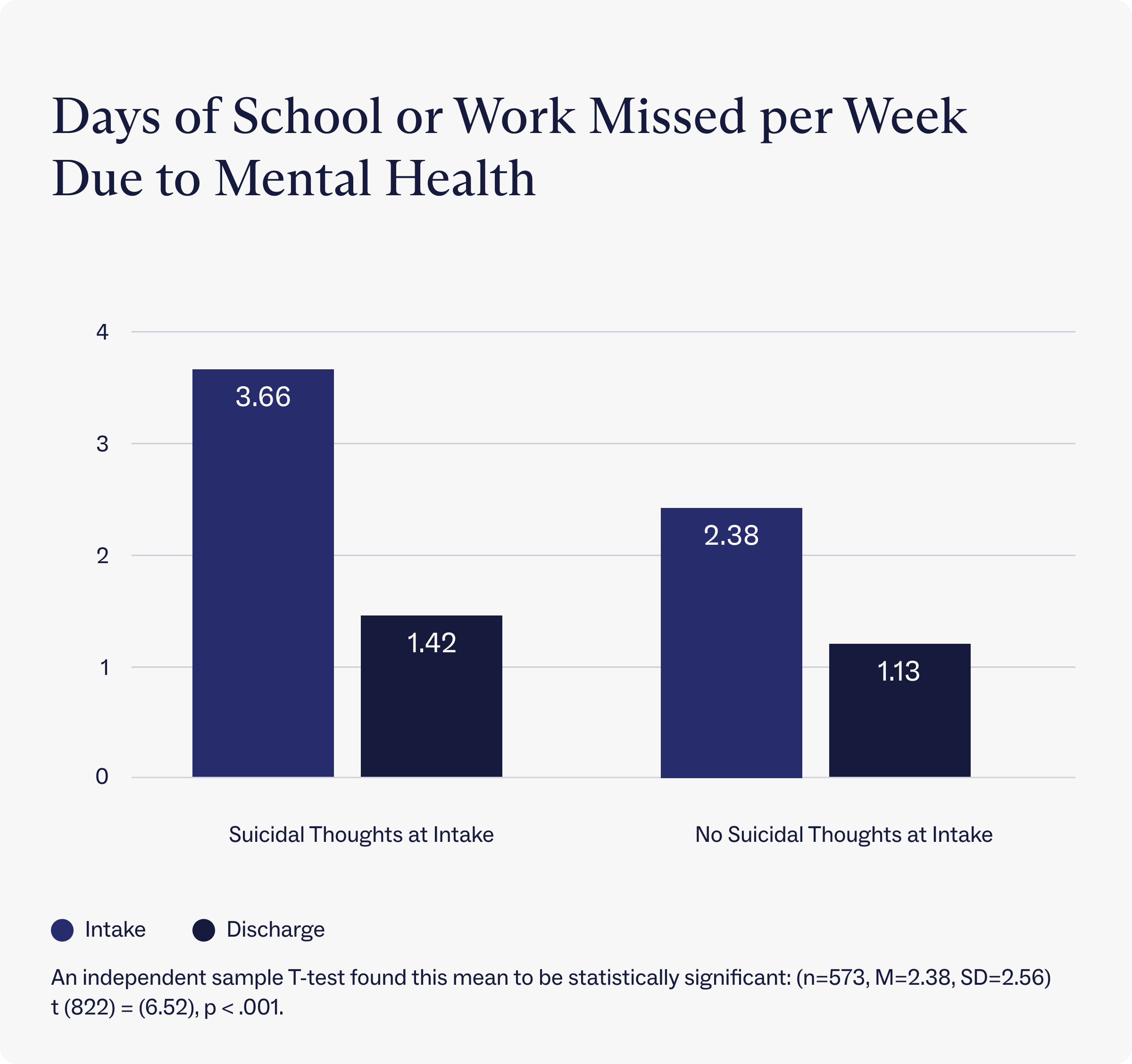

Dealing with mental health conditions, including suicidal ideation, can affect work and school life—where people spend much of their days. An analysis of clients at Charlie Health found that those who reported suicidal thoughts at intake missed an average of roughly 3 days of school or work per week due to their mental health. By contrast, clients who did not report suicidal thoughts at intake only missed about 2 days of school or work per week on average due to their mental health.

After discharging from Charlie Health, though, those who reported suicidal thoughts at intake only missed 1.42 days of school or work per week due to mental health, a reduction of 61% from intake. After treatment, clients who did not report suicidal thoughts at intake also reported a reduction in days of school or work missed. Those clients reported missing 1.13 days of school or work per week on average, a reduction of 53% since intake.

Anxiety

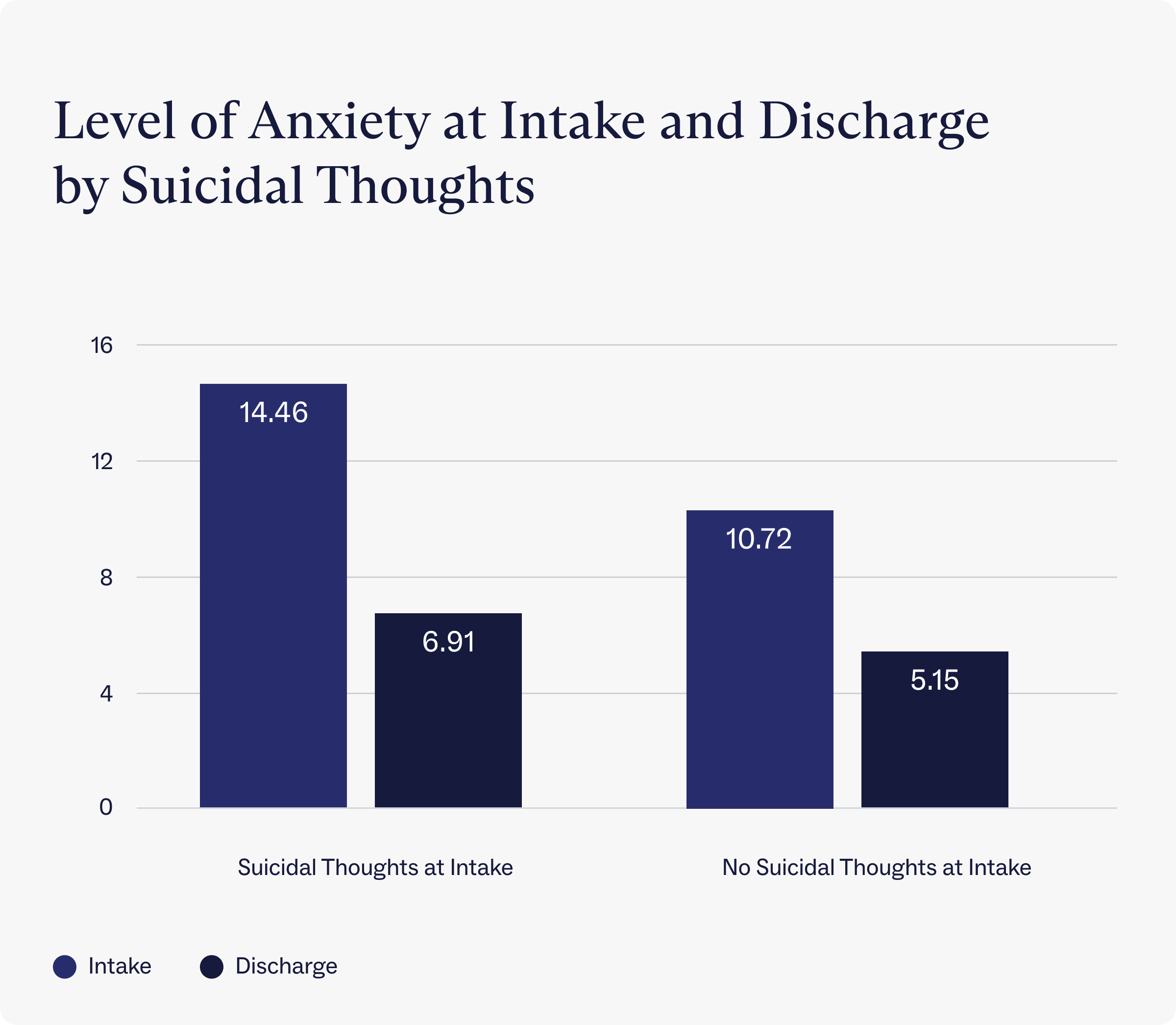

Charlie Health data show that anxiety is another key risk factor for suicide. Rates of anxiety among clients were measured using the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). In this seven-question assessment, people assign a score of 0 to 3 (corresponding to “not at all,” “several days,” more than half the days,” and “nearly every day”) to questions about their anxiety. The total GAD-7 score is the sum of the values from all seven questions. It ranges from 0 to 21, categorizing people into 4 groups ranging from “minimal anxiety” to “severe anxiety.”

On average, clients with suicidal thoughts at intake reported a GAD-7 score of 14.46, just under the “severe anxiety” threshold. By contrast, clients who did not report suicidal thoughts at intake reported “moderate anxiety” scores (10.72).

After completing treatment at Charlie Health, clients who reported suicidal thoughts at intake showed a more than 50% decrease in anxiety and scored, on average, within the GAD-7 threshold for “mild anxiety.” Even clients who did not have suicidal thoughts reported a massive decrease in anxiety at discharge, dropping to a GAD-7 score of 5.57 on average, just over the “minimal anxiety” threshold.

Suicide crisis resources

While it’s essential to understand the factors that can put someone more at risk for suicide, anyone who is in danger of harming themselves needs to get support immediately. One way to get support for this kind of mental health emergency is to contact The Suicide & Crisis Lifeline 24/7 by calling or texting 988. People who are actively suicidal may also want to call 911 or go to an emergency room for immediate care. Studies also indicate that in the short term, one effective method for preventing suicide is eliminating access to potentially lethal means, particularly firearms.

Charlie Health as a long-term solution for suicide prevention

Research shows that the only long-term solution for treating suicide is mental health intervention and treatment. One such kind of treatment is Charlie Health.

On average, clients who complete treatment at Charlie Health show a 69% reduction in suicidal ideation at discharge. And these effects are long-lasting. A year after treatment, clients maintain a 53% reduction in suicidal ideation. And a decrease in suicidal ideation corresponds with other positive mental health outcomes. Clients who attend Charlie Health show a 93% reduction in inpatient admissions, an 83% reduction in emergency room visits, a 52% reduction in self-harm, and a 47% reduction in anxiety.

How Charlie Health can support those struggling with suicide

Charlie Health provides suicide attempt survivors and those with suicidal ideation evidence-based, compassionate virtual care that works. If you or a loved one are struggling with thoughts of suicide or complex mental health concerns, Charlie Health is here to help.

Our virtual intensive outpatient program (IOP) combines group sessions, individual therapy, and family therapy that offers more support than once-weekly therapy but less oversight than inpatient treatment—the sweet spot for many suicide attempt survivors looking to transition back into their lives in a healthier, safer way. Different therapy modalities (such as DBT and CBT) are used multiple times a week in individual and group settings to provide symptom relief and promote recovery.

Fill out this short form to get started today.

References

Clarke S, Ragan E, Berk M. Management of suicidal youth. In: Clinical Handbook for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric Mood Disorders, Singh MK (Ed), American Psychiatric Association Publishing, Washington, DC 2019. p.391.

Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2011. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries 2012; 61(4), June 8, 2012. www.cdc.gov/MMWR/PDF/SS/SS6104.PDF

Wilcox HC, Kharrazi H, Wilson RF, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2016; Data linkage strategies to advance youth suicide prevention: A systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prervention Workshop

Warning signs for suicide: theory, research, and clinical applications.

Rudd MD, Berman AL, Joiner TE Jr, Nock MK, Silverman MM, Mandrusiak M, Van Orden K, Witte T

Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2006;36(3):255.

Screening for suicide risk in the pediatric emergency and acute care setting. Wintersteen MB, Diamond GS, Fein JA Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(4):398.

Shain B; COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE. Suicide and Suicide Attempts in Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016 Jul;138(1):e20161420. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1420. PMID: 27354459.

Gould MS, Marrocco FA, Kleinman M, Thomas JG, Mostkoff K, Cote J, Davies M. Evaluating iatrogenic risk of youth suicide screening programs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005 Apr 6;293(13):1635-43. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1635. PMID: 15811983.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/self-injury/symptoms-causes/syc-20350950

https://www.crisistextline.org/topics/self-harm/#what-is-self-harm-1

https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Common-with-Mental-Illness/Self-harm

https://hooleylab.psych.fas.harvard.edu/files/hooleylab/files/ndt-198806-nonsuicidal-self-injury-diagnostic-challenges-and-current-p_3.pdf?m=1596739636

https://www.charliehealth.com/post/start-the-conversation-suicide-awareness-mental-health

Hawton K. Restricting access to methods of suicide. Crisis. 2007;28 (S1):4-9.

Simon, T.R., Swann, A.C., Powell, K.E., Potter, L.B., Kresnow, M., and O’Carroll, P.W. Characteristics of Impulsive Suicide Attempts and Attempters. SLTB. 2001; 32(supp):49-59.

Personal communication, Thomas Simon, March 15, 2005.

Williams, C., Davidson, J., & Montgomery, I. Impulsive suicidal behavior. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1980;36, 90-94.

de Moore GM, Plew JD, Bray KM, and Snars JN. Survivors of self-inflicted firearm injury. A liaison psychiatry perspective. Medical journal of Australia. 1994;160(7):421-425.

Peterson L, Peterson M, O’Shanick G, and Swann A. Self-inflicted gunshot wounds: Lethality of method versus intent. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:228-231.

Eddleston M, Karunaratne A, Weerakoon M, et al. Choice of poison for intentional self-poisoning in rural Sri Lanka. Clinical Toxicology. 2006;44:283-6.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19026258/

https://healthandjusticejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40352-020-00117-3

Brent DA, Perper JA, Allman CJ, Moritz GM, Wartella ME, Zelenak JP. The presence and accessibility of firearms in the homes of adolescent suicides. A case-control study. JAMA. 1991;266(21):2989–2995[PubMed]

Rockett IRH, Caine ED. Self-injury Is the Eighth Leading Cause of Death in the United States: It Is Time to Pay Attention. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(11):1069–1070. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1418

Haukka J, Suominen K, Partonen T, Lönnqvist J. Determinants and outcomes of serious attempted suicide: a nationwide study in Finland, 1996-2003. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 May 15;167(10):1155-63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn017. Epub 2008 Mar 14. PMID: 18343881.

Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, Lonnqvist J, Malone K, Marusic A, Mehlum L, Patton G, Phillips M, Rutz W, Rihmer Z, Schmidtke A, Shaffer D, Silverman M, Takahashi Y, Varnik A, Wasserman D, Yip P, Hendin H. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005 Oct 26;294(16):2064-74. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. PMID: 16249421.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643

COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE, David A. Levine, Paula K. Braverman, William P. Adelman, Cora C. Breuner, David A. Levine, Arik V. Marcell, Pamela J. Murray, Rebecca F. O’Brien; Office-Based Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Youth. Pediatrics July 2013; 132 (1): 198–203. 10.1542/peds.2013-1282

https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html

Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, Stepney C, Inwards-Breland DJ, Ahrens K. Mental Health Outcomes in Transgender and Nonbinary Youths Receiving Gender-Affirming Care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Feb 1;5(2):e220978. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Jul 1;5(7):e2229031. PMID: 35212746; PMCID: PMC8881768.

Lipson SK, Zhou S, Abelson S, Heinze J, Jirsa M, Morigney J, Patterson A, Singh M, Eisenberg D. Trends in college student mental health and help-seeking by race/ethnicity: Findings from the national healthy minds study, 2013-2021. J Affect Disord. 2022 Jun 1;306:138-147. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.038. Epub 2022 Mar 18. PMID: 35307411; PMCID: PMC8995361.

Janiri D, Doucet GE, Pompili M, Sani G, Luna B, Brent DA, Frangou S. Risk and protective factors for childhood suicidality: a US population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Apr;7(4):317-326. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30049-3. Epub 2020 Mar 12. PMID: 32171431; PMCID: PMC7456815.

D’Anci KE, Uhl S, Giradi G, Martin C. Treatments for the Prevention and Management of Suicide: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Sep 3;171(5):334-342. doi: 10.7326/M19-0869. Epub 2019 Aug 27. PMID: 31450239.